1. Describe what this course is about, and how we'll do it.

2. Describe the scientific methods

Welcome to Biology 111: Foundations of Biology. This course is designed for students pursuing a B. S. degree, or for those pursuing another career where a "majors" course in Biology is required. Two other courses, BIO 101 and BIO 102, are also "lab-based" classes, but they are designed for non-science students. Non-science students are welcome in BIO 111 also, but there are a couple differences between these classes. First, BIO 111 is a bit more quantitative than the other classes. We will collect quantitative data, analyze the data with statistical tests, and use math throughout the course. Second, the other classes are "self-contained"; they are designed, in many ways, to be the last biology class someone might take. BIO 111 is "foundational". Like all other introductory courses in other majors, the course is designed to provide the grounding needed to succeed in additional biology courses.

This course (as well as BIO 101 and 102) earns General Education credit in the "Empirical Studies of the Natural World with lab" category. So, now that we are sure we are in the right place, let's begin.

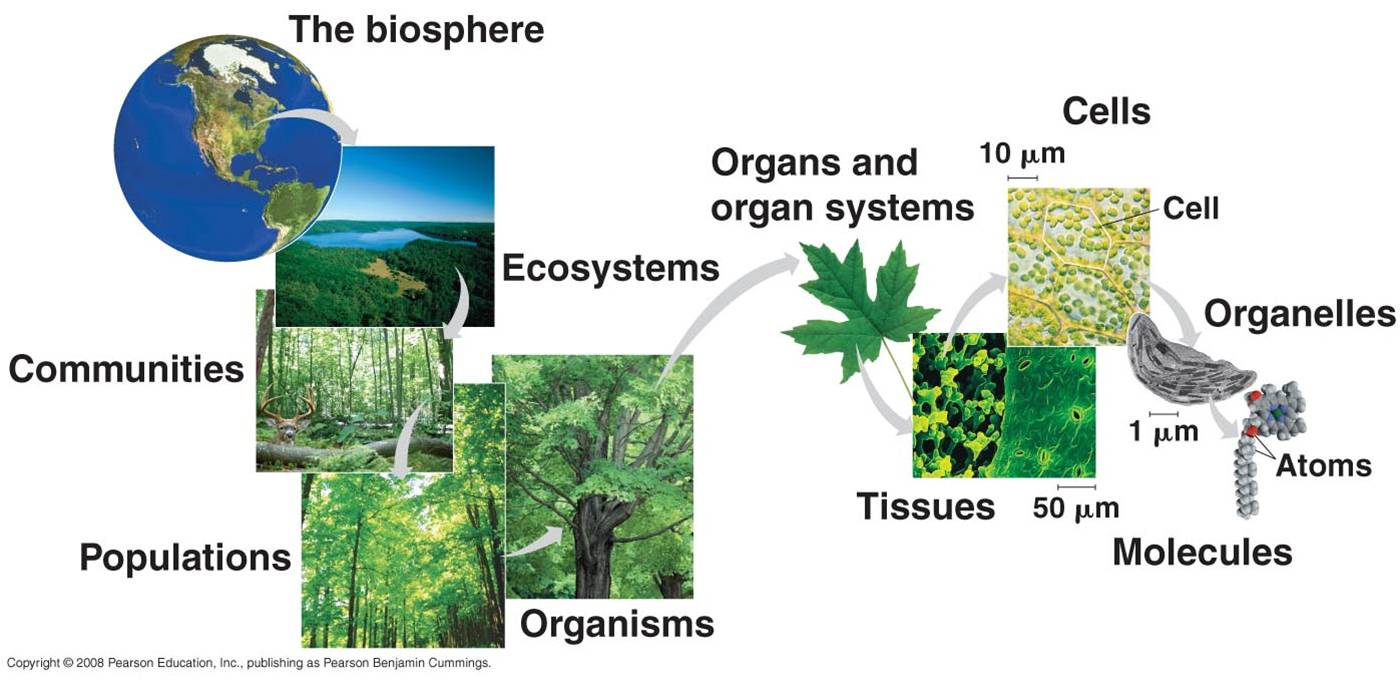

Webster's New World Dictionary defines biology as, "the science that deals with the origin, history, physical characteristics, life processes, habits, etc. of plants and animals: it includes botany and zoology." Actually, this is horrible definition! First, it seems to limit the study of biology to only plants or animals...what about bacteria, protists, and fungi? Second, although it refers to "physical characteristics" (which could be cellular) and "habits" (which could be ecological), there seems to be an implication that biology is the study of plant and animal organisms. Actually, Biology studies living systems - from the cellular to ecosystem and biospheric levels. Indeed, biochemists, molecular biologists, and geneticists also study the non-living components that make up cells.

- Our definition: "biology is the scientific study of living

systems".

- This begs two questions: What is

science and what is life?

1. What is science? Webster's: "systematized knowledge

derived from observation, study, and experimentation carried on in order to determine

the nature or principles of what is being studied. The systematized knowledge

of nature and the physical world". So, science is limited - it is limited to studying the PHYSICAL WORLD (UNIVERSE), through EXPERIMENTATION. That will be our definition: "science is the study of the physical universe through experimentation."

a. REDUCTIONISM:

b. THE COMPARATIVE METHOD:

When any complex system is considered in isolation,

the observer is impressed with its complexity, integration of function, and

internal causalities, and the very complexity of it seems to make figuring out

it's origin nearly impossible. When we ask "why an eye?" or even the more mundane

question of "How an eye?", there seems to be no place to start.

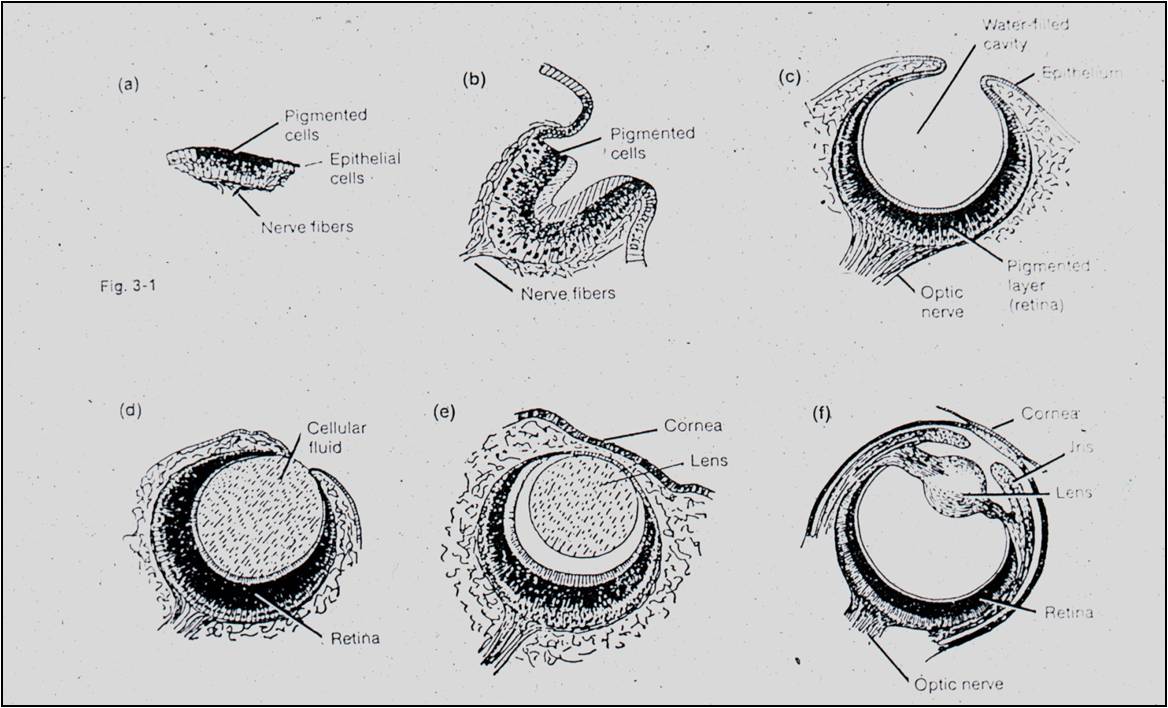

Hmmm.... retina first, lens second, humours third, cornea and muscles last.

Functionally efficient at each step, satisfying the limitations of a functional

non-random sequential process. Good answer to an initally apparently intractible,

unanswerable question using reductionism and the comparative method in an evolutionary

context. c. EXPERIMENTATION:

1) The first element is REPLICATED OBSERVATION - you have to observe something

alot of times to get a feel for which events happen concurrently and might be

putative causal agents. For instance, you might be watching the development

of a fruit fly and you might notice that the eye begins development on a rainy

day. Well, did rain cause eye development? NO WAY TO TELL. But, if you observe

eye development in 100 flies over a period of time, you will probably notice

that eye development occurs on rainy AND sunny days, so neither rain nor sun

correlates with eye development and thus are probably not causal agents. Through

careful observation and some knowledge of the system, a subset of factors possibly responsible can be determined. So, observation does

not invovle looking at ONE thing - it involves looking at MANY THINGS and observing

patterns of correlation among these things. Where to from here?

2) The second step is to construct a HYPOTHESIS; a statement of causal relationship.

What is actually causing the phenomenon that you observed?

For a hypothesis to be scientific, it must be falsifiable with evidence from the

physical world. You see, science is NOT the process of dreaming up ideas

and then only seeking data that confirms this idea. The fundamental process of science is testing falsifiable hypotheses. What

does this mean? Well, a falsifiable hypothesis is

one that could be proven false—it is a statement for which you can

envision contradictory evidence. For example, the

statement that “humans evolved from other primates” is a falsifable statement.

We can envision collecting data that would disprove it.

If, for example, we found human fossils DEEPER in sedimentary deposits

than any other primates, then this would suggest that humans lived before all

other primates and thus could NOT be descended from other primates. We TEST hypotheses by looking for BOTH contradictory and

supporting evidence in an unbiased way. So, we dig

deeper into sedimentary strata in places we haven’t dug yet.

We don’t know what is there, so it is an unbiased search.

We could find human fossils (which would disprove the hypothesis), or

we could find only other primates (which would support our hypothesis). The KEY is that, in an experiment, both falsification

and support is possible.

Science is limited to studying the physical universe; it is unable to address

questions of morality ("Is killing ever justified?"), or those dependent on the assumed existence of supernatural

agents ("Where does God live?"). However, facts drawn from science and from nature may have implications

in these areas. The physical universe is a pretty big and complex place; how

can we even begin to try and understand this seemingly limitless complexity?

Where do we begin and how do we proceed?

Science is an empirical philosophical approach, meaning that a scientific argument

or "truth claim" requires physical evidence that can be experienced

"by the senses". But science is much more than "common sense"

- in fact, it is almost the exact opposite. "Common sense" is a conclusion

or "truth claim" that is accepted based on personal observation or

opinion, alone--without thoughtful reflection or consideration of other alternatives.

So, "common sense" would tell us that the Earth is flat, the sun orbits

the Earth, solids are mostly matter (not space, as they are), and species are

unrelated. By it's very nature, science does the opposite; it necessarily creates

testable hypotheses that addresses at least one more important alternative--your

idea might be wrong. Science tries hard to exclude personal opinion or bias

in reaching a conclusion. That is why science is so quantitative and mathematical;

numbers are impersonal and are less subject to opinion. So, the goal of science

is to explain observations by testing falsifiable hypotheses of causality. "Testing"

means gathering new physical evidence that bears on this question. Over time,

scientists have found that FOUR major philosophical approaches have been very

useful in describing the universe. None are unique to scientific study, but

together they make a very powerful tool for understanding the physical universe.

If you have a complex system (and

all living systems are very complex), and you want to figure out how it works,

try to 'break it down' into smaller, less complex subsystems. If you can figure

out how the subsystems work, maybe you can then appreciate how the subsystems

relate together to function as the cohesive whole. Consider a cell; it takes

in material, break that stuff down and harvests the energy released by this

breakdown, then uses that energy to maintain its own integrity (replacing broken

stuff), and build new stuff (grow and reproduce). It is all incredibly complex,

but maybe we can get a handle on how it all happens by looking at one step at

a time.... even by looking at the structure and characteristics of what cells

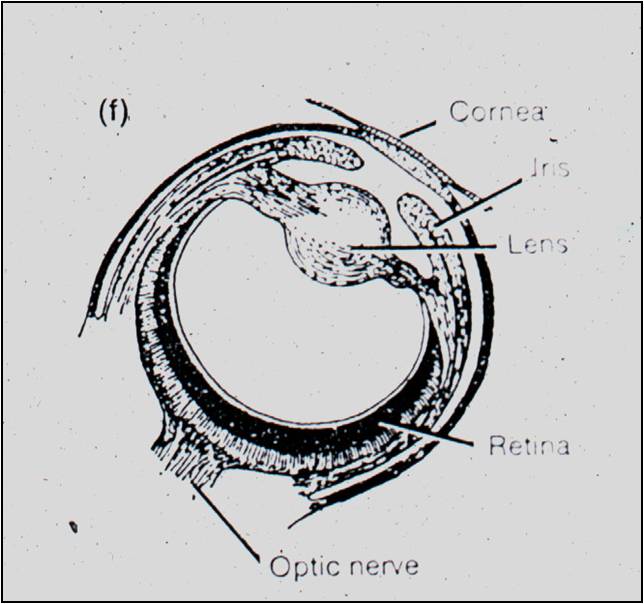

are made of - that's what we'll do in the first part of the course. Another example is the "camera eye". It is an

extraordinary organ. How does it work? Well, break it down.

There is a retina that responds to visible light by sending neural impulses

to the brain. There is a lens that focuses light on the retina.

There is an iris that regulates the amount of light entering the eye.

There is a cornea that bends the light initially, and there are two gelatinous

"humors" that give the eye shape. WOW! It is a complex system, but

by breaking it down into its component subsystems and learning what they do,

we describe--in part--how an eye works.

Another example is the "camera eye". It is an

extraordinary organ. How does it work? Well, break it down.

There is a retina that responds to visible light by sending neural impulses

to the brain. There is a lens that focuses light on the retina.

There is an iris that regulates the amount of light entering the eye.

There is a cornea that bends the light initially, and there are two gelatinous

"humors" that give the eye shape. WOW! It is a complex system, but

by breaking it down into its component subsystems and learning what they do,

we describe--in part--how an eye works.

Finally, the most direct way to tease apart causality from a nearly infinite

set of coincident events is experimentation. For instance, if you want to know

how eyes develop, well, there are an infinite set of events occuring whe an

eye is developing, including genetic events and environmental events.

Astronomy: Heliocentric Theory (no one has stood outside the solar system, but this model

predicts where the planets will be in relation to each other and the sun.)

Chemistry: Bond Theory (until 2009, no one has seen atoms bound together as molecules, but this theory predicts

which the binding properties of chemicals)

Biology: Evolutionary Theory (no one has seen a living dinosaur, but morphological, paleontological,

geological points to a relationship with birds, and this predicts where subsequent

fossils are found).

d. METHODOLOGICAL MATERIALISM:

You can only manipulate and observe physical phenomena. So, because science is limited to the study of physical, material phenomena, hypotheses regarding non-physical, non-material, or supernatural things are beyond the bounds of science, can not be addressed by scientific methodologies, and so are not scientific hypotheses. Now, this is a methodological limitation. Science does not (and methodologically can not) assert that the physical/material universe is all there is. This would be philosophical materialism. But, the physical is all that can be tested by science.

2. What is life? (next class)

Things to Know (like, without looking at your notes...):

1) Know our definitions of 'biology' , 'science', and 'theory'.

2) Understand the four philosophical approaches used in science. Don't just give a definition; be able to recognize when they are being used.

3) Know how the term 'theory' use in science, and how this differ from its common usage, as in "that is just a theory".

4) Understand

Study question:

1) Why is the comparative method so useful in biology? Why should we expect things

to be similar?

2) why 'creationism' and 'intelligent design' are not science.