|

|

|

|

|

Produced

by the Population Genetics and Evolution class, Furman University |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

Produced

by the Population Genetics and Evolution class, Furman University |

||||

|

The

Devonian: Attercopus |

|

||

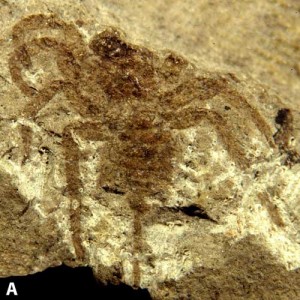

| Attercopus

fimbriungus was once believed to be the oldest-known true spider

(Strickland 2008). Recent analysis, however, showed that what was believed

to be the spinneret, the silk-producing structure that is the distinguishing

feature of modern spiders, was not a spinneret at all (Sheldon, Shear,

and Sutton 2008). Instead, they had two rows of spigots on plates located

along the underside of their abdomen (Sheldon, Shear, and Sutton 2008).

Another of the many other differences between Attercopus and

modern spiders is the presence of a long tail (ScienceDaily 2009). With

this reexamination, as well as the discovery of other spider-like organisms

that also have spigots and tails, Attercopus fimbriungus has

since been re-identified as a protospider, representing an important link

in spider evolution (Sheldon, Shear, and Sutton 2008). Attercopus

could produce sheets of silk but, without the precision that spinnerets

would provide, was unable to spin webs (ScienceDaily 2009). They possibly

used the silk to line burrows, to guide themselves back to safety in a

retreat, or to cover egg sacs (Sheldon, Shear, and Sutton 2008). Web building

would seem unlikely since flying insects would not appear until much later

in time (Strickland 2008). Page by Lin Lin Zhao |

|

| Fossil of Attercopus fimbriungus, a protospider. Photo Credit: Smithsonian.com | |

|

ScienceDaily. 2009. How the spider spun its web: ‘missing link’ in spider evolution discovered. Accessed February 22, 2010. Sheldon PA, Shear WA, and Sutton MD. 2008. Fossil evidence for the origin of spider spinnerets, and a proposed arachnid order. PNAS 105: 20781-20785. Strickland E. 2008. Spider ancestor made silk—possibly using it for sex—but couldn’t spin a web. www.discovermagazine.com. Accessed February 22, 2010. |